Fulling, Felting Your Knitting, Felted Fabric, and More Questions Answered

If you read Part 1, you already know what felt is and how to get started making it by hand. For Part 2, we’ll start with how to finish your handmade felt, or felt something you’ve knitted first.

An example of the bags I made. These are made entirely by wet felting; they start out as fluffy wool like the example in Part 1. As you can see, it’s possible to make complex sculptural shapes without any stitching or even yarn! I formed the pockets by using resists to keep the two layers from felting together where I didn’t want them to.

An example of the bags I made. These are made entirely by wet felting; they start out as fluffy wool like the example in Part 1. As you can see, it’s possible to make complex sculptural shapes without any stitching or even yarn! I formed the pockets by using resists to keep the two layers from felting together where I didn’t want them to.

What is fulling? Or, how do I felt knitting or fabric or old sweaters?

Fulling is a term used for the second stage of felting, and for felting fabrics which are already knit or woven. This makes sense because in either case, the fibers are stable enough to take some more vigorous agitation. Although, when you’re felting something like your knitting by hand, it’s still a good idea to gently encourage the fibers to cling together at first, rather than rubbing them around as hard as possible. Keep in mind that at any stage, gentle agitation can actually work better. Try it and see.

There are lots of ways to full, or harden, your felt. This is where the majority of the agitation takes place. In Mongolia (where there’s an amazing heritage of felting, think yurts), the tradition is to roll a new rug up inside an old one, and drag the bundle behind a horse!

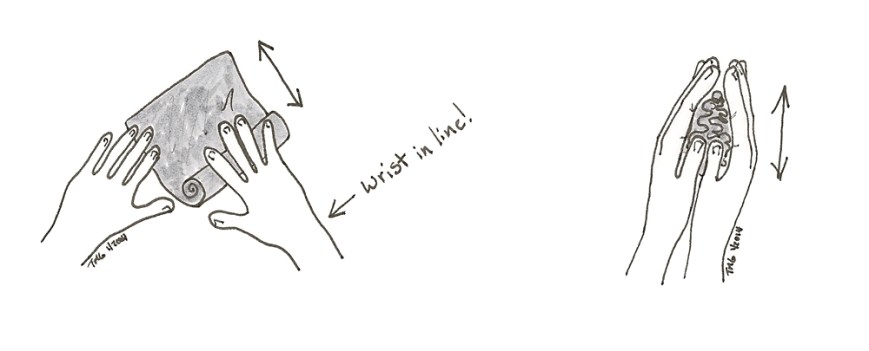

By Hand

When I’m felting knitting by hand, or fulling a felt piece like the one illustrated in Part 1, I have a bowl of water about as hot as my hands can stand. I dip the piece into the water, squeeze some of the water out, and rub it. Two effective motions are rolling, and scrunching the felt between your two hands. You can also scrub it around on the bubble wrap, or even throw it against a hard surface to get the shrinking going. Whatever you try, remember to keep your hands in alignment with your arms and wrists in good alignment.

The advantage of felting and fulling by hand is how much control you have. The exact parts of your felt you rub are the ones that shrink, and they shrink dramatically more in the specific direction you are agitating them! Try it by rubbing a corner in towards the middle of the felt, and you’ll see what I mean. For even fulling, make sure to rotate the direction in which you’re rolling and rubbing.

Stop and stretch your felt (and your hands & arms!) from time to time, stretching out your work will actually help it shrink down further.

For felting my gloves/mittens, I put them on, dunked them in the water, and rubbed them all over and around each other, concentrating on areas that I wanted to shrink more, and alternating taking them off for stretching and rolling with more rubbing while on my hands.

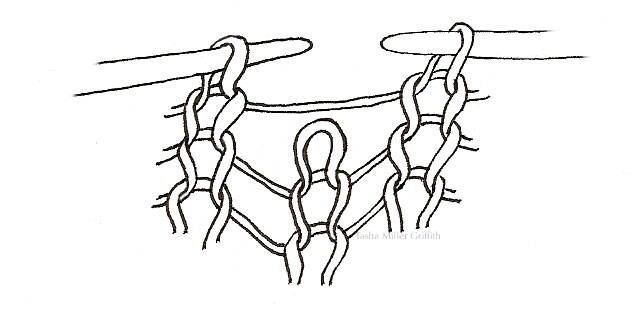

In this wet-felted color sample, you can see how fibers from each side of the piece worked their way to the other side with thorough felting.

In this wet-felted color sample, you can see how fibers from each side of the piece worked their way to the other side with thorough felting.

In the washing machine

You can also shrink knitting, fabric, and even hand made felt that’s getting good and sturdy, in the washing machine. Proving that agitation trumps any and all other factors, even though the fibers are swimming in water and the water may not be that hot, you can quickly get dramatic results. The downside is that you don’t have much control over what happens. I usually use the washer to help with fulling when I’m felting something big, but I check on it every few minutes, getting the felt out of the water and stretching or rubbing certain parts to help it take on the shape I want. Top-loading washers produce the most agitation, and are the easiest to use for checking the felt frequently. Front-loading washers also work, especially if you are trying to felt something as much as possible, so you’re planning to leave it in for the whole cycle.

Set the water level for lowest amount that will cover whatever you’re trying to felt, and the most soil/most agitation setting, with hot water. Put your piece in a zippered pillowcase, to prevent the wooly lint which some pieces shed a lot of from clogging the washer pump (ask me how I know about that!). If your washer has a removable lint filter, you don’t need the pillowcase, just be sure to clean the filter when you’re done.

I don’t recommend felting large pieces of fabric in the washing machine, the agitation is just too uneven over such a large piece, and it will probably come out with some areas much more felted than others. If you want to felt fabric for a sewing project, try cutting it into smaller pieces first (be sure to account for shrinkage when planning the size of the pieces, see below). Even then, you’ll get the most even results if you can alternate being in the washer with stretching and rolling the pieces.

Some people use the dryer to felt as well. If you’re trying to shrink your felt as much as possible, throwing it the dryer certainly won’t hurt. Also feel free to experiment with putting damp felt in the dryer, and checking on it frequently the same way you would for felting in the washer.

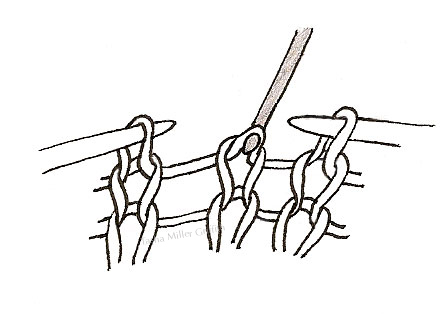

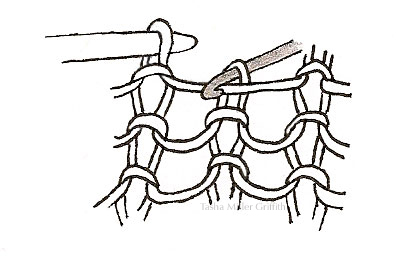

The body of this sweater felted well, except where the stitches were held in place by the sewn-in tag. Since those fibers weren’t free to rub against each other and felt, they still look the same as they did before going through a few hot washes!

The body of this sweater felted well, except where the stitches were held in place by the sewn-in tag. Since those fibers weren’t free to rub against each other and felt, they still look the same as they did before going through a few hot washes!

Will felt keep shrinking forever?

No. At some point, the fibers have locked down as much as they are ever going to, and you really can’t get your piece any smaller, even if you want to.

Can I decide that my felt is done even if it hasn’t shrunk/hardened as much as it could?

Absolutely. As long as it’s sturdy enough for its intended use, you can stop whenever it’s the size and thickness you want. Sometimes the maximum that your felt could shrink would be much too thick and stiff for what you intend, or just too small, especially for felting knitting and fabric. On the other hand, if you are making hand-felted boots or handbags, you’ll probably want to plan on the maximum amount of felting you can get, so that as many fibers as possible will be locked in, and the finished item will be as long-wearing as possible.

How much will my felt shrink?

It depends on a dizzying number of factors, but there is one sure way to find out: test it, by making a sample and measuring it before and after, as I illustrated in my post about the magic purple mittens. This method works for wet felting too, just measure the dimensions of the wool you lay out before you felt it. If you’re trying to get a sense of how much fiber you used, any dry felt weighs the same as the fiber used to make it.

Wool from different breeds of sheep felts dramatically differently, some from sheep raised for meat may not felt at all! Even different individual sheep can produce wool which felts differently from the next sheep over. The hat at the beginning of Part 1 is Churro wool, which shrinks a lot, as you can see from the pattern!

If you’re buying yarn or fabric to felt, unless it’s from a local herd, you may not know what type of sheep it comes from, but most quality wool will felt to some degree. The yarn or fabric should be at least 50% wool, alpaca, cashmere, or other feltable critter, and not be treated (“superwash” etc.) to prevent felting. Bleaching can be hard on the fiber scales that make felt work, so lighter colors often take longer to felt. Like I said, there are a lot of factors, so if it matters what size the final felt is, test first!

When I was looking for a wool to make my wet felted bags from, I made a lot of samples!

When I was looking for a wool to make my wet felted bags from, I made a lot of samples!

Can felt happen by accident, or with wear?

Definitely. As you’ve seen by now, the conditions for felt are readily available in your washing machine, which can be disastrous if your nice sweater accidentally gets in there. And, as I found out the hard way, even if it seems like a garment made from wool fabric is not felting, over many many washes, it eventually will (illustrations and happy ending here).

I also know from experience that a garment can felt as you wear it. I have a pair of alpaca and wool blend fingerless mitts that, as they are exposed to warmth and moisture from my skin, and agitation as I wear them while I grab my keys, the steering wheel, etc., are slowly becoming more solid. We shall see what the end result is. This is something I’m really interested in at the moment, so stay tuned for more findings. For now, my best advice is: don’t make an article that will be exposed to felting conditions out of a material that felts easily, or plan for shrinkage and felt it first.

What should I do with my felt when it’s done?

Let it go through the spin cycle, or roll it up in an old towel and squash it, to get out as much extra water as you can. In this damp state, the felt is super malleable, so plan on doing some final shaping. You can rub, tug, scrunch, stretch, and otherwise push the felt around into exactly the shape you’d like. If you’re felting something like a hat, it helps to have an object to “block” (shape) it on, try a bowl a little bigger around than your head. When you get you new felt shaped just as you would like, leave it alone to dry. If the felt is thick, this can take a couple of days.

Once the felt is dry, you still have another chance to shape and smooth it, with steam from your iron. All wool responds especially well to steam (think about tailoring), but on felted wool steam is a minor miracle. It can straighten out lumpy areas and smooth the whole texture of your felt. Placing the iron right on the felt will also smooth and flatten the surface fibers, so if you don’t want that, hold the iron above the surface to fill the felt with steam, then put the iron down, and shape with your hands.

Don’t I need soap to felt?

My current experience says not necessarily, except under special circumstances. Historically, all kinds of harsh chemicals were used in felting, to roughen up the fibers’ scales and speed up the process. These were also highly toxic. Most felters now just use a mild soap. Olive oil soap and liquid soap are popular choices. This soap doesn’t do much beyond decreasing the surface tension of the water. Lately I have been felting mostly without soap, and I haven’t noticed a difference between using it and not using it in my studio. You may find soap more helpful than I do, depending on your wool and your water. Don’t add too much though, if the fibers are too slippery they won’t want to grab on to each other.

When you are hand felting, if your hands are sticking to the fibers rather than sliding over them, a little soap on your hands should help. A mixture of solid soap and water can be a very effective “glue” if you are hand felting two things that don’t want to stick together.

If you are felting in the washing machine, you definitely do not need to add soap. There will be enough left from the last load to make plenty of foam.

If you do use a soap that’s alkaline (most are), make sure to rinse it out thoroughly when you are done felting. Animal fibers, like your own hair and skin, are slightly acidic, and being left in an alkaline environment for long periods can damage them. Include a splash of vinegar or lemon juice in the last rinse, and let the felt soak in it for a few minutes to neutralize any remaining alkalinity.

I made this bag from felted wool sweaters.

I made this bag from felted wool sweaters.

Why would I want some felt anyway?

Felt is fabulous! It’s a dream to work with. As you sew it, you can ease in what seems like an impossibly large piece onto a small one, just using your fingers. It doesn’t ravel when you cut it. It wears like iron (assuming it’s tightly fulled). It’s so insulating that I can iron the outside of one of the wet-felted bags, with lots of steam, with my hand inside, and feel nothing for minutes. It’s breathable and odor-resistant and has all the other lovely properties of natural fibers. Plus it’s beautiful, natural, and fascinating. It can be sculpture with fiber. It’s the perfect next stage for a sweater that’s been attacked by moths or pets, or just has cuffs too worn out to repair—felt it and make it into something else.

Finally, how not to felt

To care for precious article you’d rather not felt, basically do the opposite of what you would to felt it. Hand wash it very gently: place it in water with a little bit of pH neutral soap. Let it soak clean, press down gently to move the water through it, and drain the water off without agitating. Keep the rinse water the same temperature as the wash (lukewarm is fine) and avoid letting the water run directly on the article. Spin it out (spin only) in the washer, or roll in a towel and mash on the roll. Reshape, and leave to dry flat.

Further reading

My favorite felting book is Uniquely Felt by Christine White. It covers, in detail, methods for just about every type of wet felting you could think of. Pat Spark, who I mentioned in Part 1, has been at the forefront of bring felting to the internet since the very beginning, and she has a ton of useful info on her site.

I packed as much as I could in here without going into exhaustive detail, so I hope it’s helpful and not too overwhelming. If you have more felt questions, send them my way!

Ok, so I admit this is not the greatest picture, but this is me with the amazing

Ok, so I admit this is not the greatest picture, but this is me with the amazing