In which I remodel my mittens to make them better than ever, and show you how to calculate shrinkage when felting your knitting.

My friend Tom once commented that many of my clothes have stories behind them, and these mittens are no exception! In fact, I’m going to tone it down here, story-wise, and stick to only the most interesting and relevant of the many angles I could go for.

A Very Short History of the Original Mittens

I started knitting these as my take-along project on our trip to Italy in February of 2010. I knitted the main parts from yarns that we dyed the first time I ever did natural dyeing, with my grandmother and a bunch of dear family members in 2008. (I’m telling you, I’m skipping a lot of stories here). My goal was glove fingers for finer dexterity, that could also be covered by a mitten flip-top for extra warmth. Typically for me, I consulted a few patterns, but didn’t end up really using any of them. I didn’t have enough purple for the fingers and the flap, and because I love purple and green together (one of my favorite color combos for the hats) I decided to get green yarn. No one else was impressed with this decision, and I can now admit that one of my students at the time probably put it best when she said they looked like “dead fingers.” So, moving on, when I discovered that they were too slippery to drive in, I sewed on a bunch of patches from faux suede samples in different colors. Ignoring whether or not this made the green fingers look any better, and also the fact that all the fingers had come out too short after felting, I wore them all the time, all over the place, skiing, shoveling snow, etc., through last winter. By the end of that season, one of the fingers had developed a rather large (and cold) hole in the end.

A Plan for New and Improved Mittens

When I got them out this fall for the season, the more I thought about it, the more I wanted to do more than just fix the hole. You see, if I was going to fix the hole, it made way more sense to knit on a little more finger, so that it would be actually the right length. And, it would be ridiculous to do that for only one finger. And, if I did it for the rest of the fingers, I would either have more green fingers or an even more ridiculous color mash-up than before. I decided to start over on the fingers, and this time, do the math.

As fate would have it, last winter I sent my blog friend Alessa some American patterns, and she sent me some yarn and other lovely stuff from Germany (these mittens really are more full of stories than average, even for me). Thanks Alessa! One skein of the yarn (on the left below) was a lovely variegated purple in 100% alpaca. Alpaca felts like a dream, and is just as soft felted as not. I saw it in my yarn bin and knew it would be perfect for new fingers.

Is that not the most-awesome-looking tin of chocolate?

Is that not the most-awesome-looking tin of chocolate?

How to Calculate Shrinkage for Felting Knitting

Lots of times I tell my students that knitting can either be all math; full of charts, calculations, and exact numbers of stitches, or no math at all; flowing along and decreasing when it looks right to you. In my mind, the happiest mix is somewhere in the middle. When you’re felting, it really helps to have a least a little math, which comes from making a sample in your intended yarn and measuring how much it shrinks, especially if you need it to come out a certain size. (I neglected to do this for the first fingers, and you saw how that went.)

I started out with a tighter gauge, then decided to increase my needle size, because looser knitting will felt faster (you can see from the before and after that it also affects the percentage of shrinkage). I’m using two strands of the yarn since it was fairly fine, and I wanted the fingers to be nice and thick and warm when finished. You don’t have to take a photo, but do measure and draw around your sample. Also make a note of how many stitches are in your sample, they will disappear into the felted texture and you won’t be able to tell later. (This is about the smallest sample that will give you an accurate idea.)

Before felting:

After felting: (As usual, click on the pictures to enlarge if you wish.)

Here’s the math part, it’s not too scary: divide the felted measurement by the unfelted measurement, to get the percent of the original measurement after shrinking. F/U = % I did this across my various measurements and got an average of 79% for the width, 84% for the height. I wanted both, because I had noticed when felting the fingers the first time that they wanted to shrink more in height than in width, no matter how I stretched them out, which meant that I had not added enough extra knitting in that dimension.

Now that you have your percentage, apply it like this (there was algebra involved but I did it for you): the unfelted measurement (the one you want so that you know how much to knit before it shrinks) equals the felted measurement (how big you want it to end up) divided by your percentage of shrinkage (.79 or .84 in my example). U = F/% Clear as mud? Try it, you’ll see what I mean. You end up with a number a bit bigger than the felted/finished number you put in. You can check it by putting it back in the first formula and see if you get the right percentage.

For my finished/felted measurements, I used the width of the previous fingers (by now chopped off), which I liked, and measured the height of my fingers sticking out of the mittens, adding a little extra for the thick knitted fabric to go over the top. I calculated the unfelted measurements, then used the gauge from my sample to figure out how many stitches to use for each finger. You can’t have a fraction of a stitch, so round up or down, whichever is closer or you want to err on the side of. I knit until each finger was about the calculated unfelted height, erring on the side of a bit extra at the top, which turned out to be a good idea!

Just in case, I made one finger as test (the index finger on the right below) and felted it before knitting the others. It came out great.

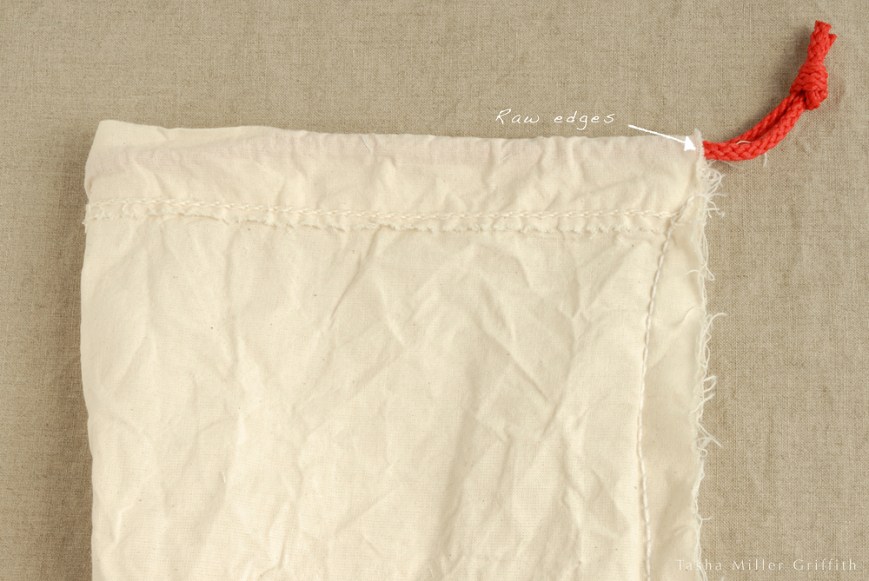

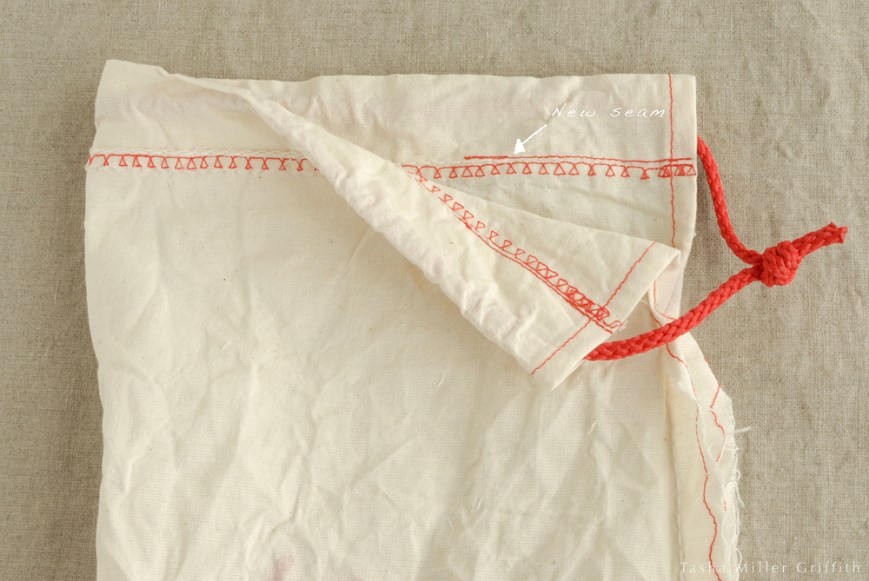

Even though the old fingers were felted on, I was able to snip the green stitches and pull them out, leaving the purple ones which I could pick up and knit from. It helped that the palms never got totally felted.

Even though the old fingers were felted on, I was able to snip the green stitches and pull them out, leaving the purple ones which I could pick up and knit from. It helped that the palms never got totally felted.

Other Improvements

The thumbs were too short as well, plus worn mostly through in one spot from gripping. And having only one layer of knitting (the part between the thumb and palm where the stitches tend to stretch open no less) meant that my thumbs were sometimes cold. I fixed all that. At this point, there was no stopping. Since the thumbs were somewhat loose, I decided to knit inner layers for them. I thought that I might need to slash the top of the mitten flap and extend it too, but after felting the fingers, it fit snugly over them, which would be warm, and I could add a bit of ribbing on the palm side for a little more length and to help hold the flap down. Neither of these new additions would be felted, and both were small, so this was the no-math part. I made adjustments visually, pulling something out if it didn’t seem right, and tried on the thumbs a lot to fit the shape to my hand.

This may be hard to believe, but according to my notes, the wool I used for the new ribbing is the same as the original flap and thumb! So it has definitely faded with sun and wear and washing. Fortunately I like both colors.

This may be hard to believe, but according to my notes, the wool I used for the new ribbing is the same as the original flap and thumb! So it has definitely faded with sun and wear and washing. Fortunately I like both colors.

A Minor Miracle of Purple Suede

Finally, I needed something for grip on the fingers and palms. (I’m telling this story whole, it’s a good one.) I want to be able to drive and grab ski poles and my keys, etc., and I didn’t want to go back to the multicolored bits of Ultrasuede. I briefly considered using some light green suede elbow patches I got along with a sweater for recycling . . . and was fortunately dissuaded by friends. What I ideally wanted was something that would match the mittens.

Almost on a whim, I dropped into a rather old-school shop downtown, which sells saddles and leather and a few seemingly random bolts of blanket wool and skeins of rug yarn. I remembered that the last time I was there, over a decade ago, they had a bin of leather and suede scraps, and I thought if they still did, I might be able to find something close. I was the only one in the little shop, not too long before closing, and the woman working said that no, they didn’t have any scraps. I had the mittens with me, I showed her what I wanted to do. Suede and leather started at half a hide for $24, there were black and green and red . . . and at the end of the rack, four smaller, scrappier pieces, all in dusky, slightly mottled shades of purple. Not just purple, four distinct purples that each were so exactly what I needed that they looked like they were dyed to coordinate with the mittens, and left on the end of the rack by magic. “Oh,” she said, “You could use those! They’re $9 each. We sold all the red, all the black . . .” Hardly believing my good fortune, I picked the color I liked best out of the thicker two (two were quite thin), paid for it, and practically skipped down the street towards my car. A few times, when I’ve been intensely searching for a supply I cannot find, probably which doesn’t exist, I’ve dreamt that I went into a shop and found exactly that thing, only to wake up disappointed. This is the only time, so far, it’s ever happened in my waking life. I have a rather large piece of somewhat smelly purple suede left in my studio to prove it!

I love love love these mittens. I finished sewing on the suede over our family Thanksgiving trip, and just in time too, when we got back our town had a major cold snap, not getting above freezing at any time for over a week, unlike our usual mountain cold nights but mild days. I’ve worn these cross-country skiing, I wore them to art walk downtown at night (during the below-freezing week), shoveling snow, driving, and never one cold finger have I had! Felted alpaca is like little down blankets for your fingers. I can easily wriggle my fingers out of the mitten top for fine tasks without using the other hand. Having placed the suede patches where the wear was on the old fingers, plus the part of my palm that I use when I grip things—surprise!—they are in the perfect spots. I recommend the inside of the thumb especially.

If you want to make your own version, I’d start with a glove pattern you like. Either refer to a flip-top mitten pattern, or make up the flap as you go (Basically: I picked up sts across the back of the hand, cast on across the front and did a few rounds of short rows for a curved shape, joined everything into a round and knit, decreasing following the shape of the fingers underneath).

I realize that I haven’t talked about the actual felting, in fact that felting is probably the thing I know the most about that appears the least on this blog. Maybe I’ll do something about that in 2014.

In the meantime, if you have any questions about making mittens or felting in general, feel free to let me know!

Happy Solstice, everyone!